Daniel Rodriguez’s paintings of groups and grids of people and places are all about human systems of organisation: parking spaces, employee charts, school graduations and reunions. Each painting takes a distanced view on its subject, both in compositional and in formal terms. ‘Edificio’, a painting of a modernist apartment block complete with hanging laundry, bikes and pot plants, is shown in its entirety, as though at long range, and rendered in a characteristically washed-out and flattened brushstroke in chalky pinks and blues. That distancing (in one work, ’Marcha’, a large crowd is seen directly from above, as though through the eyes of a pigeon contemplating its next target) shouldn’t be mistaken for coldness, though, as it might be in the works of other painters working in a similarly tentative, faux-naive style. Rodriguez’s works are full of a kind of warm amusement, a sort of fascinated attention to the habits of human beings that is both empathetic and oddly alien.

In ‘Reunion’, a grid of headshots (evidently drawn, however loosely, from a photographic source) sits on a light grey ground, like a corporate advent calendar (Christmas Eve: Helen from HR; Boxing Day: Roger from Retailing). It’s one of many winks and nods in Rodriguez’s work towards the kind of hardcore asceticism of modernist painters like Agnes Martin or Sol LeWitt. You might say that the grid, paragon of hands-off seventies conceptual art, is the butt of the joke here, and Rodriguez’s aerial shots of car parks (complete with cack-handed alignments and nudging bumpers) work as sly parodies of that sort of high-minded practice. You could even see those blanched and stiffened faces as headshots of the upper eschalons of the contemporary art world, each one an uncomfortable bureaucrat with a bad tie.

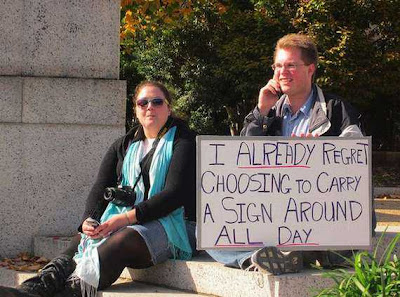

However, Rodriguez’s works are more than mere in-jokes: each painting is a small celebration of the various real (as opposed to virtual) communities that form an ordinary life. Look at the painting ‘Amigos de la Tierra’. A gathering of studiously casual people (employees, it’s assumed, of the eponymous environmental charity; a blaring green background makes the point pretty clear) are seen from above. The source must be a photo taken from a balcony or second-floor window, perhaps to be displayed in the office’s reception area. The employees squint and rock on their heels while waiting for the signal to disperse and get back to work. Like a bisected anthill, the painting records an exposure of the realities of any corporate organisation: that it’s (horrifyingly) made up of people like you. And the title of ‘Empleados del Mes’ – ‘Employee of the Month’ – initially surprises: each face is rendered with gleeful satirical detail, so that the parade of boss-eyed and bad-haired heads looks more like a police line-up or sex offenders register. Yet as with all Rodriguez’s works, it’s ourselves we see reflected back, however painfully. As Demetri Martin says, “’Employee of the month’ is a good example of how someone can be a winner and a loser at the same time”.

Published on Saatchi Online, Dec 2010.

View here.